The Bofulvus Manifesto, Parts 1-3

The following is a draft of an essay by the Bofulvus Collective, written for the first issue of an upcoming MSP zine for the DCC RPG.

“Remember the good old days, when adventures were underground, NPCs were there to be killed, and the finale of every dungeon was the dragon on the 20th level? Those days are back.”

“Fantasy roleplaying split from historical wargames sometime in the early 1970s, although retaining clear signs of their common ancestry. [… I]t didn’t take long for creative ideas to start rolling in. But for a brief, glorious while, the pastime existed in its primitive state, unburdened and uncomplicated.”

“Once upon a time, D&D was a game about exploring dungeons.”

-Unknown RPG commentator

INTRODUCTION

Our game group, the Bofulvus Collective (BFC), started playing the DCC RPG in 2018, about six years after its launch and about six years before we started writing this essay. That's the longest period that anyone in the group has played TTRPGs consistently, and it's given us a chance to develop our thinking about what we like in a game.

The BFC manifesto collects a number of ideas of ours on topics pertaining to gaming and creating game material. It's nowhere near as expansive as, say, Daniel J. Bishop's excellent Dispatches from the Raven Crowking, but we think it goes a long way toward communicating our point of view about The Way Things Should Be in TTRPGs.

1. WHY DCC?

There are a lot of tabletop RPGs available today. A LOT.

You have the many editions of the World's Most Popular Fantasy Role-playing Game (now in its 51st year!), its early (contemporary) clones and copycats, the flood of recently penned OSR (Old-School Renaissance/Revival) games, and hundreds of other TTRPGs themed after everything from the Alien movies to Watership Down.

So why do we play DCC as our main game?

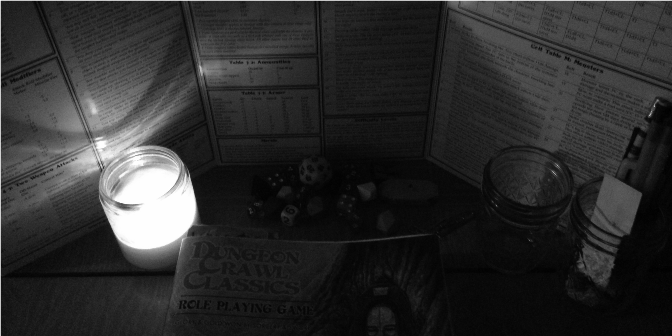

In the summer of 2018, two of us were fortunate to stumble upon a hard copy of the DCC RPG rulebook (on sale for half price!) at a chain bookstore. Why it was there, and why we, not being active gamers at the time, happened to be browsing the games rack, the world may never know, particularly as the rest of the games section wasn't very indie-oriented, but there it was, beckoning to us: the Purple-Rimmed Face-Door of Adventure. Picking it up, we were overwhelmed by the loads of cool illustrations and the fact that it looked like D&D, but all in one book.

Flash back to the 1990s, when one of us played a game of AD&D 2E at a friend's house and found it surprisingly fun. However, subsequently trying to get into the hobby independently proved to be an expensive and frustrating experience of wading through confusing changes in rules editions, the baffling "basic" vs. "advanced" scenario, a mountain of sourcebooks and novel-length modules, and no idea whatsoever of how to put it all together. The books came into the house via Borders and left a few years later via eBay, mostly never having been played.

DCC, on the other hand, simplified the essence of what was fun and exciting about it into a new and better game, and going online to look for adventure modules and supplementary materials to incorporate into our sessions blew our expectations out of the water. There was a thriving community of publishers making both commercial and DIY content for this game, which centered on an “Appendix N” sword-and-sorcery theme by default, in all genres and with widely varying levels of complexity and sophistication, but almost always with lots of creativity. Many modules later, we still feel DCC is both enjoyable enough as-is and adaptable enough to keep on playing it.

2. ON THE DM PROBLEM, OR JUDGES JUST WANNA HAVE FUN.

In the original 1974 D&D rules, co-authors Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax wrote in regard to preparing a campaign, “The referee bears the entire burden here [emphasis added], but if care and thought are used, the reward will more than repay him.” They then went on to describe the laborious but potentially highly interesting process of drawing out underworld maps, setting monsters and treasure about them, placing its entrance within an overworld or wilderness setting, and so on. Here, the word, “burden,” always has stood out to us.

It should be noted that when this phrase was written, Arneson and Gygax reportedly had in mind that every game group would create all of their own adventure scenarios and campaign worlds from scratch. They did not, in other words, envision the widespread publication of pre-written modules and sourcebooks – so much so that when representatives of the Wee Warriors company approached them about licensing the first-ever third-party D&D adventure module, 1975's Palace of the Vampire Queen, Arneson and Gygax replied something to the effect of, “You can have the license, but who’s going to pay money for something they can make themselves?”

Truly, how disappointing it would be to bring such a product to market only to discover that no one wanted to buy it because they already had plenty of their own stuff. What happened, though, was that for the same reason why Hungry Man dinners are still sold in the freezer aisle, the idea was a hit and paved the way for untold thousands of published adventures to come, both from third parties and from game rules designers themselves.

While today, we might chuckle at the ironic lack of imagination in this department from two pioneers of imagination-based gaming, what's not so funny to us is how most game modules for any TTRPG system have been written. Specifically, although these are game materials necessarily meant to be played at a table by a party of gamers, not merely read silently by an individual like a novel, they tend to have much more in common with the latter in the way they come across and how, in practical terms, they lend themselves (or don't) to being played. We believe that the root of the problem lies in the typical Gygaxian style of module presentation.

To be clear, Gary Gygax wrote some amazing game scenarios, and we don't mean at all to slight the content of his contributions to the body of TTRPG material or Gary’s abilities as a game runner. All we're talking about when we reference “Gygaxian module presentation” is the style and formatting in which his modules were published, which has since been copied with few deviations by almost every other TTRPG author. We want to change this.

If you've seen Gary Gygax at an RPG convention either in person or in photos, what probably comes to mind is a gigantic loose-leaf binder overflowing with maps and scraps of text. When you're the author of those details, the pages full of notes simply serve as a reminder and guide to what you've already created in your mind, but when someone else hands you their binder and says, “Run this,” you may find yourself returning to that word, burden.

When you zap a Hungry Man and tear back the film, the selling point is that you didn't have to cook it yourself. You're eating it because someone else put it together for you, and you wanted to enjoy it without doing the work. Likewise with a video game: you spend money on the game so that you can stick it in your console or load it in your computer without doing the coding yourself. You just pay your money and then sit back and enjoy it.

Somehow though, with TTRPGs, we've been tolerating a model for half a century in which judges shell out for pre-written modules and then do almost as much work to prep them for actual play as if we'd created them ourselves, and maybe more on some of the more elaborate ones! It's the only scenario in which people wanting to enjoy a game are expected to do homework, and often times extensive amounts of it, before we can get into the actual experience of sharing it with others, which is where the fun actually happens. This isn't the case with board games or any other game, and in our opinion, it's neither desirable nor necessary for a TTRPG if done differently.

What we believe to have happened, way back in the roots of this game of a new type, is that the role of writer and judge, originally assumed always to be the same person, were never properly separated for prewritten modules.

We know that D&D was created with the ironclad idea that every judge would be the author of their own adventures. And again, when the judge is the originator of these details, all of the written notes and play aids function merely as reminders to enable them to keep serving up the particulars of the scenario as the other players explore. Want to change something on the fly? No problem! As the author of the scenario, the judge already has a sense of where there's leeway, and they already know alternate scenarios they considered when designing it. When the judge is the writer, and the writer is the judge, there's almost no danger of on-the-spot contradiction because the odds of the judge tripping themself up in the details of their own story are very low.

What we've noticed, though, is that when an outside writer – anyone other than the judge – enters the picture and does the designing of an adventure, we often see a lack of consideration for the judge. The writer may essentially crowd them out and end up trying to judge the adventure through them, leaving little room for the judge's experience of play. Two people in this case end up vying for control behind the judge's screen: writer and judge. We refer to this conflict as the Tyranny of the Writer, and it can be miserable for the player who serves as judge.

Let's remember that the judge necessarily already serves as a quantitative human calculator of game details, the qualitative final arbiter of What Happened, and the person most responsible for the players having a good time overall, which is already a lot in itself and potentially enough to be somewhat stressful. If we now add to that the expectation of doing hours' to days' worth of extensive prep work (key word: work) in order to internalize someone else's creation to the point of being able to run it without contradicting any important plot points, thus reducing the potential for spontaneity at the game table, can we even still call this experience “playing”? (A great example was on the now-deleted YouTube channel, Jon's DnD Vlog, where the author showed the thick binder of notes he prepared so as to be able to run the classic, 128-page (!) AD&D module, The Temple of Elemental Evil.)

The writer may have written the module, and they may in fact be the best person to run it, but the reality is, they aren't running it. They know it, and we know it, so why don't judges demand that these things work better out of the box for judges? Would we accept any other game – gin rummy, flashlight tag, or ice hockey – on this basis? If not, why do we put up with it for TTRPGs? Why not demand that modules not only not eschew the micromanaging and leave more room for the judge but also be functionally presented to read better and be more playable on the fly, like the game aid (and not the novel) that they're intended to be? Isn’t it possible? It is.

3. INTRODUCING THE IAG METHOD

Our solution is something we call the Improvised Adventure Game, or IAG, method. You'll see this style in the adventure scenarios presented later in this issue, “Secret of the Ape-Men” and “The Springs Under Nirigo.”

IAG modules are meant to be played with the judge having done zero work in advance of the game session. “All play and no work – for the judge” could be its motto. At the same time, IAG provides the judge with well-crafted, detailed, pre-written adventures rather than the hastily scripted “pamphlet modules” typically marketed as “low prep” which more or less require the judge to come up with everything themself and are hardly worth the cost.

What IAG seeks, in short, is balance and agreement between the writer and the judge. The writer wants to create a world for others to explore and adapt into their own, unique experiences at the game table. The judge wants to save time by having a writer put together a rewarding adventure scenario they can sit down and play with friends. IAG allows for the writer to present a fully playable world without overburdening the judge, but how?

What IAG aims to do first and foremost is to rearrange the Gygaxian standard of module layout into something more usable at the game table, like the play aid it is, and not a novella that needs to be predigested. To accomplish this, it takes into consideration the form the module takes: a two-paged, 8.5” x 11” magazine format.

Judges, please answer the following quickly, without overthinking: while sitting at the game table, do you enjoy flipping back and forth, front to back, through a module to get from the maps to the area descriptions?

We don't. Consequently, drawing inspiration from the aforementioned D&D module, Palace of the Vampire Queen, the only module we've ever seen which consistently does this (but even then, not quite perfectly), IAG modules place the area map (underworld level(s), wilderness hexes, or town overview) on the left page of the open booklet and the room, hex, or building key on the right side – the way the judge actually holds the book while playing. How this has never become standard, we don't know, but we're fixing it in our game materials.

The result is that the judge can focus clearly on the area at hand, without having to flip through pages of text describing other areas of the dungeon, and think ahead easily to what the PCs will encounter next. Likewise, all of the area descriptions are viewable at a glance in the area key on the opposite page: just enough to play with.

This brings us to IAG's second major point. Having streamlined the presentation of each area of the adventure to be viewable without flipping pages, IAG makes a point of presenting just enough info to the judge to enable them to present a module area to the other players without straining either to incorporate reams of mostly superfluous details from paragraphs of judge-only text while dividing one's attention between that and the actions the players are declaring, or trying to generate too many new game details of their own. Here, the “I” in IAG stands out.

The idea behind the restrained yet adequate level of detail for each item in the map key is that the judge is a creative player who’s capable of doing the basic task of the game: improvising to role-play scenarios based on thoughtfully sculpted prompts provided by the writer. The dimensions of the room are provided by the map. The ambiance is sketched by the level description. Any monsters, traps, and items are listed on the room key, and the rest is up to the judge. No overly elaborate if-then logic trees. No extensive backstory fluff the PCs can't discover. Just what's there, described as simply as possible (and no more simply), much like a prompt from the audience on Whose Line Is It Anyway? That is, after all, what we're here for: not reading the PCs a story but rocking & rolling.

We know, and firmly believe that it is Right and Good, that the judge, while rendering the area description and exploring the environment along with the other players, will get all kinds of interesting ideas running through their mind that they will want to execute, and we not only absolutely do not want to constrain those possibilities with excessive prefabbed details but believe that those ideas, coming from the judge, serve as the lifeblood of the fun. If we're serious about experiencing TTRPGs as collaborative storytelling, then the Tyranny of the Writer is unacceptable; it will not do. The job of the writer is to build a sturdy playhouse for the romp. The job of the judge is to bring it to life, including a lot of themself in that. After all, no one plays simply to be a human game console.

Thirdly (and lastly, for now), IAG extends the collaborative spirit beyond the individual module to the campaign by allowing for a rotating judge. Word in 2025 is that D&D is now considering a way to bring in some sort of a collaborative DM experience to their game, and good for them, finally! After all, they've only had 51 years to work on it. For our part, it's one of the first things we wanted to do, and we believe that it stems logically from the same approach which led us to develop points one and two above. How?

An IAG module is one which is well-developed by the writer, who provides the skeleton and viscera of the adventure but leaves room for the judge to play with the skin and other details as they wish. It also allows the judge to experience the adventure just as the other players do: as a surprise. IAG modules include opening tips for the judge to consult while the other players are sharpening their pencils, but otherwise, judges go in sans spoilers and sans backstory, just with what they need to know to make the adventure their own without messing it up. All info can be discovered by PCs in-game, or else it's not part of the game, and crucially, campaign segments are written so as to tease but not to spoil future segments. Once one module in a campaign has concluded, someone else can take a turn in the judge's seat to run the next installment.